The Zone of Interest, Oppenheimer, and American Fiction

Three recent, much-lauded films leave a viewer indifferent at best

The Zone of Interest, directed by Jonathan Glazer.

The only things The Zone of Interest take from the late Martin Amis’s terrific novel of the same title are the title, the time and location, and the focus on the private lives of the Auschwitz commandant and his family. Glazer pretty much did away with the characters and plot of Amis’s novel, which included three protagonists, each providing separate narratives. Glazer eliminates that story structure in favor of a more tightly woven, minimalist focus on the family life of Rudolf Höss, the real-life commandant of Auschwitz, who has installed his wife and children in a lovely home and garden separated from the death camp – the inside of which we never see – only by a wall.

What we see and what we hear and what we intuit are all different things. The best thing The Zone of Interest has going for it is the sound design by Johnnie Burn. The entire mood and the impact of what is happening inside Auschwitz is almost entirely communicated by the continuous soundtrack of cries, shouts, moans, groans, gunshots, screams, and otherworldly sounds that float over the wall into the Höss’s yard in the same manner that ash from the death camp’s crematoria leaves a coasting of dust in their backyard, their soil, their swimming pool, even on their hands and heads.

Yet they love the house where they live and the garden Mrs. Höss works in most days, seemingly oblivious to what is happening just over the wall. But she is not oblivious; the Höss’s have servants and day workers who are camp inmates, and evidence of the mass destruction of the camp’s prisoners shows up in the form of stray bones and body parts in the nearby river, as well as that ash and the sounds.

Even in its modesty, the film has ambitions to be an art film, to make a quiet statement about “the banality of evil.” In my case, those ambitions were undercut by my familiarity with Amis’s novel. Perhaps coming to the film cold, with no preconceptions, might leave a viewer more affected by the clinical portrayal of life beside Auschwitz. The movie has garnered many rave reviews, but in a film like this it is hard to delineate between reviews based upon the “importance” or “relevance” of the subject matter and the actual success or failure of the work of art to stand on its own two feet. In the end, it left me wanting something else, something more, something that Glazer presumably was not interested in exploring in depth, in favor of his visual poem.

Oppenheimer, directed by Christopher Nolan. Starring Cillian Murphy.

Speaking of “important” films that rely on the import of their subject matter to give them gravity, the much-lauded Oppenheimer – nominated for 13 Academy Awards, including Best Picture, Director, Actor, and Adapted Screenplay – was an infuriating film. Tracing the development of the atomic bomb under the direction of J. Robert Oppenheimer, director Christopher Nolan plays a little loose with the historical record, but that in itself is not what shipwrecked the film for me.

I love the actor Cillian Murphy, but Nolan’s treatment of the actor – as opposed to the character he plays – is symbolic of everything that is wrong with Nolan’s treatment of this story, and, I submit, what mars Nolan’s movies in general. Christopher Nolan has little to no interest in humans or humanity. People are just vehicles in his movies, which flatten out characters and even make them look like aliens. Murphy does have bright blue eyes that are almost superhuman in the way they glow, but Nolan films Murphy – and his eyes – as if they are emitting blue light throughout the entirety of the film. Maybe Nolan thought that would be a clever way of implying that some kind of thermonuclear reaction was taking place inside of Oppenheimer’s brain. Instead, it renders the character as almost an alien, as in an extra-terrestrial. Sure, Oppenheimer was “an alien” in any number of ways, but it did not serve Murphy or the film to portray him as a non-human.

A streak of misanthropy runs through Oppenheimer as it does most of Nolan’s movies, which is why those that embrace his love of ideas and superhuman notions work best. As for Oppenheimer, it is a piss-poor pairing of director and subject matter.

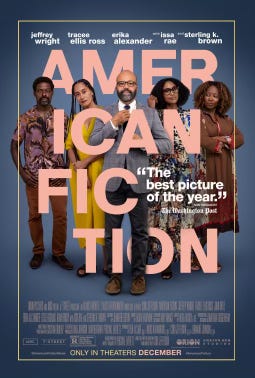

American Fiction, directed by Cord Jefferson. Starring Jeffrey Wright.

Cord Jefferson shows promise with American Fiction, his feature-film debut, something of a satire of the publishing industry but really of greater aspects of American culture at large.

Based loosely on the novel Erasure by Percival Everett, the movie finds the main character, Thelonious “Monk” Ellison (played by Jeffrey Wright), stuck in a netherland of being a well-respected but poorly selling novelist. On a lark, Ellison dashes off the kind of crass, stereotype-based novel that sells in the millions, and publishes it under a pseudonym. Spoiler alert: Ellison’s work, intended as a prank, catches on in a bigger way than he ever could have imagined, and his life and relationships are turned upside down.

The supporting cast, including Tracee Ellis Ross, Issa Rae, Sterling K. Brown, John Ortiz, Erika Alexander, Leslie Uggams, Adam Brody, and Keith David, are all fine, but even as satire, the story stretches all sense of credibility – and to work as satire, it must be credible, or at least more balanced. Perhaps American Fiction might have worked better with fewer characters, digging deeper into just a few of the most important relationships instead of spinning out in multiple directions that merely detract from the main story’s overall impact.

Hey, did you like this edition of Everything Is Broken? If so, please consider clicking on the “LIKE” button at the very end of this message. It matters to the gods of Substack.

Roll Call: Founding Members

Anne Fredericks

Anonymous (6)

Erik Bruun

Nadine Habousha Cohen

Fred Collins

Fluffforager

Benno Friedman

Amy and Howard Friedner

Jackie and Larry Horn

Richard Koplin

Paul Paradiso

Steve and Helice Picheny

David Rubman

Spencertown Academy Arts Center

Elisa Spungen and Rob Bildner/Berkshires Farm Table Cookbook

Julie Abraham Stone

Mary Herr Tally