ILLUMINATIONS: Why I Just Can’t Relate

Must we 'identify with' fictional characters in order to love them?

IT USED TO drive me crazy when people would criticize a book or a movie by complaining that they could not “relate” to the protagonist. Since when did that become a requirement of storytelling? Do people “relate” to Frodo or Bilbo Baggins? To Tom Jones or Jay Gatsby? To Anna Karenina or Mme. Bovary? Isn’t the whole point of storytelling to create fictional characters who are different from ourselves, who take us out of ourselves, who suggest other ways of thinking and being?

I understand that in all these characters there are elements with which people can identify. Searching for something. Triumphing against adversity. Overcoming stacked odds. Running against the grain. Defying expectations. We relate to these larger-than-life characters and stories through a successful combination of “relatability” and a compelling narrative.

But then how to explain my enduring attraction to characters like Raskolnikov (in Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment) and Meursault (in Albert Camus’ The Stranger)? Vito Corleone (in The Godfather) and Thomas Newton (in Nicolas Roeg’s film The Man Who Fell to Earth)? Cold-blooded murderers. Alienated expatriates. Literal aliens. In what manner are these characters “relatable”?

Well, for one, if you have ever felt stuck or alienated from people or your surroundings—as if you speak a different language from the vast majority of those around you—you can relate to the ennui shared by the characters played by Bill Murray and Scarlett Johansson in Sofia Coppola’s Lost in Translation. The ennui is the very thing that unites them in an unusual, improbable shared bond over the course of a few nights dithering aimlessly in Tokyo.

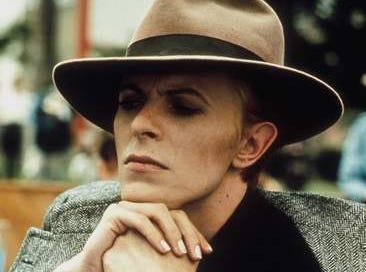

If you’ve ever felt like you come from another planet, that you have dropped into a family or a town or a situation that is utterly inexplicable and foreign to you and to which you could not possibly belong, and all you want to do is find a way to get back to your real home and family, then you can “identify with” Thomas Newton. (It helps if you are played by David Bowie.)

And if you have ever been pushed to the point of rage or absurdity (or both), you might find the most horrible actions of Meursault and Raskolnikov to be, if not justifiable, at least … relatable.

But do I really “relate” to these loathsome and despicable characters? I suppose in some form or fashion I empathize with or am drawn to aspects of their personalities—their angst and alienation and sense of otherness, primarily. The situations that writers and filmmakers devise for such characters are just that—devices. The extreme behaviors they portray is the stuff of drama. In this manner, I am willing to overlook their depravity, their amorality, their sins—if we are allowed to use that term anymore—as fanciful inventions. A wise writer friend once told me that the key to compelling fiction—and this goes for any art form, really—is exaggeration: to heighten the stakes beyond quotidian reality while still maintaining plausibility.

When an artist pulls that off successfully, I can relate as much to the artist as to the invented character. That is the true mark of genius, and it is what makes me want to read the next book or watch the next movie. It is that which inspires, in the original, archaic sense of the term: to give the breath of life.

And now, inhale….