How to Play Nicely

Recent visits to the theater to see 'The Sign in Sidney Brustein’s Window'; 'The Seagull/Woodstock, NY'; and 'The Wife of Willesden'

I have a love-hate relationship with theater. There are rare times when staged plays can be sublime and transcendent, when the script is smart, funny, and profound, when the performances are pitch-perfect, when all the cogs in the wheel that comprise a production are running smoothly and efficiently, when a viewer gets wholly caught up in the drama taking place onstage, losing a sense of one’s own consciousness and for an hour or two inhabiting the world of the playwright, director, producer, and/or actors.

Alas, this is not a common occurrence. Theater is one of the most unforgiving of arts. There are so many elements that go into staging a play that if just one is off it can throw the entire production off kilter. It could be just one weak performance in an ensemble that is otherwise terrific. It could be slow or non-existent pacing. The experience of seeing a play can even be ruined by disruptive audience behavior. While it is no fault of anyone involved in the production, the cluelessness of theatergoers who refuse (or don’t even know how) to turn off their phones, to not talk to their neighbors during the performance, and not to pick up a call and have a phone conversation during the performance (I assume all regular theatergoers have experienced this by now) – any of these incidents can turn an evening at the theater into a big disappointment.

More common are productions that, while not “great,” are good enough to satisfy a playgoer. Maybe there was a standout performance that more than compensated for a weak one in the cast. Maybe the writing was so witty and brilliant that lines and phrases just exploded like firecrackers in spite of themselves. Maybe directorial choices were so unique and inventive that you were just dazzled by the experience. I’m not sure what percentage of productions fall into this category. I don’t think it reaches a half, and it may be only about a quarter.

In my experience, the vast majority of theater productions fall into a different category, a catch-all basin of mediocrity or worse. You’ve all seen these: Plays that fail to get off the ground; didactic or message-based plays that sacrifice character for cause; unconvincing performances; technically hobbled productions; staging that lacks a coherent vision or aesthetic; and plays that seem more like TV movies of the week or afterschool specials than works that cry out for or benefit from live performance.

Playgoing is, at best, a crapshoot. And the odds are stacked against the playgoer. Yet, we continue to be drawn to the stage by the mere hope that maybe lightning will strike this time out, that everything will come together the way it can and should and one will leave the theater fully entertained, provoked, and mystified by the magic that great theater relies upon.

I have been thinking about these things lately after a rare and sudden burst of playgoing, prompted in major part by my wife, who finds ways to enjoy performance that I can no longer – if I ever could -- access. (I suspect my resistance to going to the theater is fed largely by the been-there, done-that feeling resulting from a lifetime of reviewing all manners of live performance, including music, dance, theater, and experimental works.)

Our theatrical spree, which involved four trips to New York City from our home in Hudson, N.Y., began with Tom Stoppard’s Leopoldstadt, which I have already written about. (You can find that here.) I was so blown away by that play and production that I think it somewhat loosened my resistance to going to the theater. I said yes, therefore, to going back to the city to see the revival of Lorraine Hansberry’s rarely-produced The Sign in Sidney Brustein’s Window at BAM; The Seagull/Woodstock, NY by the New Group; and The Wife of Willesden, the first play by novelist/essayist Zadie Smith, again at BAM.

The Sign in Sidney Brustein’s Window seemed promising. For one, it starred Oscar Isaac and Rachel Brosnahan. I had seen and appreciated the former in a number of movies and TV series and was primed to enjoy his performance. I have come to learn that Rachel Brosnahan may have been the bigger box-office draw, acclaimed for her titular role in the recurring TV series The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel, which I have not seen. I enjoyed Isaac’s performance immensely; he really drove the story, at least in the play’s first half, and I was drawn in by his passion and idealism, even when it was delivered on trumpets of loud pontificating. Where the play failed for me was in the second half, when the naturalistic approach of what we had seen until that point was suddenly swapped for a psychedelic, fever-dream sequence that seemed to come out of nowhere. It seemed like a cheap way to deal with the arrival of a new character who unsettled the balance that had prevailed in the first act. In the end, I was glad to have seen Isaac’s performance, and the acting was top-notch throughout the ensemble with one lone exception – that of a stiff, awkward Julian DeNiro, who may have been to the manor born but on the basis of this performance, not to the manner. The play, which I saw at BAM’s Harvey Theatre, is about to reopen for a “strictly limited engagement” on Broadway.

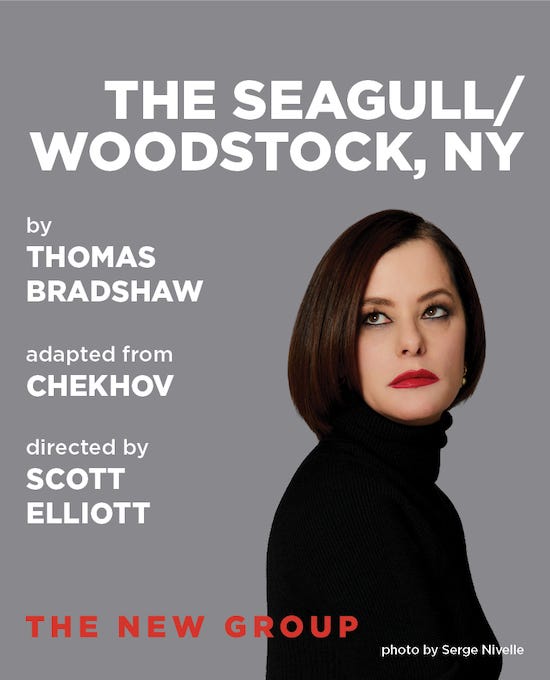

Next up was The Seagull/Woodstock, NY, which runs for a few more weeks at the Signature Theatre. I am generally well-disposed to reinterpretations or reimaginings of classic works, and as the title indicates, this is an adaptation by Thomas Bradshaw of Chekhov’s original, relocated to the Hudson Valley of today and featuring a cast playing modern-day theater people, writers, artists, and hangers-on. The play stars indie-film icon Parker Posey, who is fabulous in the lead role of Irene, an over-the-top narcissistic actress trying to reboot her acting career. Unfortunately, some odd casting renders much of the drama of relationships unbelievable, in terms of age and personality. The production is somewhat self-conscious -- with a number of plays-within-plays — but not in a bad way. But the play was deeply marred when I saw it, well into its run, by actors seemingly talking at each other rather than conversing, with infuriating pauses in the space between where one finished a statement and the other replied. These were not the fruitful, ominous, significant pauses of Pinter; rather, they bespoke actors uncomfortable in their roles or unable to assimilate their lines into an organic whole.

As I said, I have nothing against and even enjoy adaptations and updates of previous works. But if you had tried to sell me on The Wife of Willesden on the basis of it being a modern adaptation of Chaucer’s The Wife of Bath, I would have said no thank you. But if you had tried to sell me on it – or indeed, on anything – on the basis of it being written by Zadie Smith, I’m there. I am a huge fan of Smith’s novels, stories, and essays, and if she decides to dip her toe into the world of playwriting with this odd, uninviting (to me) choice of source material, far be it from me to argue.

So we found ourselves back in the Harvey Theatre at BAM last weekend to see this raucous, bawdy, colorful, musical, sexy romp of a play by Smith, beautifully acted by the stunning Clare Perkins in the titular role and supported by a talented, skillful cast handling multiple roles. Smith swapped out the Chaucerian language for a fusion of modern dialect of North London and Kingston, Jamaica, rendered loosely in couplets but without any sing-songy affect (one could easily not even realize that the text is written in couplets; I just know that because I bought a copy of the script). The play is a feminist tour-de-force, celebrating female strength, independence, and sexuality while denigrating attempts to suppress or eliminate those aspects of women.

If Smith’s play lacks some mastery over traditional theatrical elements, it more than compensates with its, well, theatricality. Dance, music, outrageous costumes, audience members seated onstage … all these devices combined for a complete theatrical experience, delivered through Smith’s typically smart, witty text and her gift for wordplay. The Wife of Willesden is not a great play, and it may be just a one-off venture for Zadie Smith, but it certainly is the most entertaining two hours I have spent in the theater in many months. Which now leaves me back where I began – do I continue to risk mediocrity in the hopes of another lightning strike?

Having started my career with a desire to be a theater director, I've always found entering a theater, particularly an empty one, to be a practically mystical experience, a place where one expects miracles to happen. Alas, miracles are rare. Several years ago, my wife and I went to a whirlwind of plays on Broadway. Tragically, no miracles were to be found. It soured me quite a bit on going to see plays, and an even greater reluctance to see anything on Broadway. The price/reward differential was far too great. I will go to see plays locally these days, which generally cost far less than Broadway. Some of them have been acceptable, at least when thinking of the cost/benefit relationship. But too many are just plain bad. It's discouraging.