Book Review: 'The Oppermanns' by Lion Feuchtwanger

This gripping page-turner from 1933 reads like today's headlines.

(Saturday, March 30, 2024) HUDSON, N.Y. – The most urgent novel I have read so far this year is a ninety-plus-years-old newly reissued translation of a German-language book first published in Amsterdam in 1933.

Lion Feuchtwanger’s The Oppermanns is many books at once: a family epic, a breathless suspense thriller, and a first-hand account of how a civilized democracy turns into a ruthless authoritarian state in the course of a single year. Nine months, to be more precise.

This was exactly the fate of Germany at the time Feuchtwanger was writing his novel, from late 1932 to the late summer of 1933. By the early 1930s, Feuchtwanger had established himself as a playwright and one of Germany’s best-selling novelists. As novelist Joshua Cohen writes in his introduction, “Feuchtwanger wrote The Oppermanns in real time, as the events he was writing about were still unfolding, and even while he was suffering the same tragedies as his characters: in 1933, his property in Berlin was seized; his books were purged from German libraries and burned; he was banned from publishing in the Reich; and he was stripped of his German citizenship.” Feuchtwanger’s lightly fictionalized – and quite artful – story was based upon the daily realities of German politics, ideology, and law (or lack of such) and their effects on the day-to-day life of the German nation’s Jewish population along with that of leftists, Communists, homosexuals, and anyone deemed by Adolf Hitler to be a threat to Germany.

It is a story we have seen and read before, most recently in the form of Tom Stoppard’s poignant play, Leopoldstadt, which covers a lot of the same territory. (One cannot imagine that Stoppard had not read The Oppermanns before writing Leopoldstadt). But remarkably, Feuchtwanger completed his novel before the year was out in 1933. In other words, he wrote this tale of the speedy, hurtling train that would eventually lead to the destruction of European Jewry years before the elements of the “Final Solution” were put into place, years before almost anyone could ever dream that such a thing would happen. Feuchtwanger had no way of knowing where things were headed, but in his cataloging of the daily slights and insults and (what we now call) microaggressions that would lead to the catastrophe of the Shoah he seems to have intuited the fate of his family, friends, and his fellow German Jews who had attained success in German society, in business, the arts, education, government, medicine, and the military such that they were nearly indistinguishable, at least socially, from non-Jewish Germans.

But The Oppermanns proves to have been about even more than all that. Reading it today, one recognizes how easily a nation of democratic ideals and practice dating back several hundred years could in a matter of months, one small step at a time, do a full 180-degree turn toward fascist dictatorship, even in its earliest manifestations proving disruptive, violent, and deadly to a population and a world seemingly totally unawares and indifferent to their fate. As such, and due to Feuchtwanger’s style, the book reads like a warning for contemporary readers, this year in the United States in particular. In 1933, Feuchtwanger showed how it was beginning to happen there; read today, miraculously across time, his novel brilliantly explicates how it not only can but is happening here. To quote the headline of a recent review in The Atlantic, The Oppermans explicates “what it feels like when fascism starts.”

As New York Times critic Pamela Paul wrote: “It’s been nearly 90 years since its publication, but reading it now is like staring into the worst of next week.”

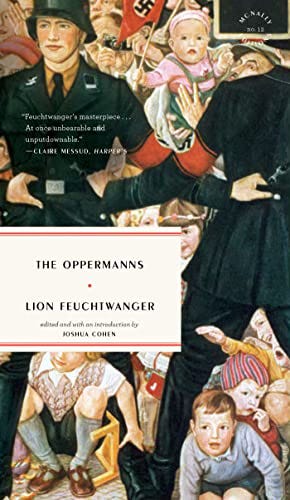

This current version of The Oppermanns, with a revised translation and introduction by Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist Joshua Cohen, is published in a handsome, fetching package with an affordable list price of only $18 by McNally Editions, which, somewhat like New York Review Books, “reissues books that are not widely known but stood the test of time, that remain as singular and engaging as when they were written.” The Oppermanns totally fits that bill.

I have written elsewhere against judging art for its timeliness or relevance. If The Oppermanns was not such an artful, gripping read, it would be neither or it would not matter. But, as Kirkus wrote of it: “It’s hard to imagine a 90-year-old book being more timely.” That is both our ultimate good luck and our incredible misfortune.

Hey, did you like this edition of Everything Is Broken? If so, please consider clicking on the “LIKE” button at the very end of this message. It matters to the gods of Substack.

Roll Call: Founding Members

Anne Fredericks

Anonymous (7)

Erik Bruun

Nadine Habousha Cohen

Fred Collins

Fluffforager

Benno Friedman

Amy and Howard Friedner

Jackie and Larry Horn

Richard Koplin

Paul Paradiso

Steve and Helice Picheny

David Rubman

Spencertown Academy Arts Center

Elisa Spungen and Rob Bildner/Berkshires Farm Table Cookbook

Julie Abraham Stone

Mary Herr Tally

"The Oppermanns" has just joined my must-read list. I've been recommending Sinclair Lewis's "It Can't Happen Here" for years.